Nestlé sought to register as a three-dimensional trademark the shape of the KIT KAT chocolate-coated biscuits, used since 1935 in the UK.

Cadbury opposed to this registration, and the examiner upheld the opposition, estimating that (i) this sign was devoid of inherent distinctive character and that (ii) it had not acquired such a character following the use which had been made of it, and (iii) consists of both the shape which results from the nature of the goods themselves and the shape which is necessary to obtain a technical result.

Nestlé appealed that decision to the High Court of Justice, which referred the following questions to the Court for a preliminary ruling (ECJ, 16 sept. 2015, Case C‑215/14, Société des Produits Nestlé SA v. Cadbury UK Ltd) :

- “In order to establish that a trade mark has acquired distinctive character following the use that had been made of it within the meaning of Article 3(3) of [the Trade Marks Directive], is it sufficient for the applicant for registration to prove that at the relevant date a significant proportion of the relevant class of persons recognise the mark and associate it with the applicant’s goods in the sense that, if they were to consider who marketed goods bearing that mark, they would identify the applicant; or must the applicant prove that a significant proportion of the relevant class of persons rely] upon the mark (as opposed to any other trade marks which may also be present) as indicating the origin of the goods?

- Where a shape consists of three essential features, one of which results from the nature of the goods themselves and two of which are necessary to obtain a technical result, is registration of that shape as a trade mark precluded by Article 3(1)(e)(i) and/or (ii) of [the Trade Marks Directive]?

- Should Article 3(1)(e)(ii) of [the Trade Marks Directive] be interpreted as precluding registration of shapes which are necessary to obtain a technical result with regard to the manner in which the goods are manufactured as opposed to the manner in which the goods function?”

The issue in this case has been raised before but remains decisive: is it possible for an undertaking to secure a permanent monopoly by registering a three-dimensional sign as a trade mark?

Since a sign which is barred from registration under Article 3(1)(e) can never acquire a distinctive character by the use made of it, the Court changes the order of the referred questions, first analysing the second and third questions, relating to the interpretation of Article 3(1)(e), and then examining the first question.

Second question

According to Article 3(1)(e), shall not be registered signs which consist exclusively of i) the shape which results from the nature of the goods themselves, ii) the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result, iii) the shape which gives substantial value to the goods.

The grounds of refusal aim to prevent the exclusive and permanent right which a trade mark confers from enabling to extend indefinitely the life of other IP rights which the EU legislature has sought to limit in time. Otherwise, it would prevent competitors from freely offering for sale products incorporating such technical solutions or functional characteristics in competition with the proprietor of the trade mark.

The Court states that, if the grounds for refusal may not be applied cumulatively to the same shape, however at least one of the grounds for refusal of registration set out in that provision must be fully applicable to the shape at issue.

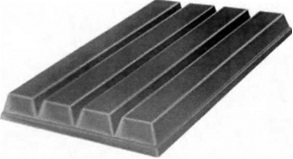

In the present case, the examiner found that the shape in respect of which registration was sought had three features:

- The basic rectangular slab shape which results from the nature of the goods themselves;

- The presence, position and depth of the grooves running along the length of the bar, and

- The number of grooves, which, together with the width of the bar, determine the number of “fingers”. Those shapes are considered as necessary to obtain a technical result.

Since none of the grounds fully applies to the shape, the trademark should not be refused in this regard.

Third question

According to the Court, “from the consumer’s perspective, the manner in which the goods function is decisive and their method of manufacture is not important.”

Burying the criteria of the multiplicity of possible forms, the Court stresses that “the registration of a sign consisting of a shape attributable solely to the technical result must be refused even if that technical result can be achieved by other shapes, and consequently by other manufacturing methods.”

The Court interprets literally Article 3(1)(e)(ii) and excludes from its scope shapes which result from the manufacturing process: “Article 3(1)(e)(ii) of Directive 2008/95, under which registration may be refused of signs consisting exclusively of the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result, must be interpreted as referring only to the manner in which the goods at issue function and it does not apply to the manner in which the goods are manufactured.”

First question

To evidence if the trademark has acquired a distinctive character through the use made of it, the applicant must prove that the shape for which Nestlé seeks registration as a trade mark, when used independently of its packaging or of any reference to the term “KIT KAT”, serves to identify the product, to the exclusion of any other trade mark which may also be present, as being, without any possibility of confusion, the KIT KAT wafer bar sold by Nestlé.

Nestlé had already been subjected to the same evidentiary issue with the catch-phrase HAVE A BREAK. Regardless of whether that use is as part of another registered trade mark or in conjunction with such a mark, the trade mark applicant must prove that the relevant class of persons perceive the goods or services designated exclusively by the mark applied for, as opposed to any other mark which might also be present, as originating from a particular company.

That is indeed the essence of trademark law.

© [INSCRIPTA]